(PART ONE)

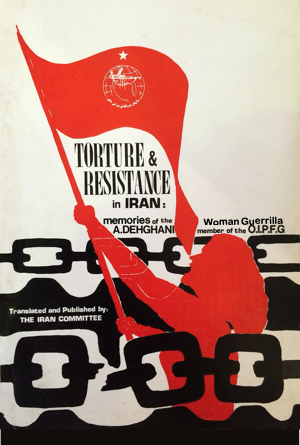

Torture and Resistance In Iran

(HEMASEYEH MOGHAVEMAT)

Written by: comrade Ashraf Dehghani

Eary 1970s

To:

… all the heroes of the masses who, martyred under torture, or facing murder squads, raised the red flag of their cause,

… all those dedicated revolutionaries, who died fighting the enemy of the people, and watered the tree of our people’s liberating revolution,

… all the political prisoners whose resistance and fortitude strengthen the people’s front, and to all those warriors of the masses, who have joined the path to people’s liberation … the path of revolution.

Iran, my land, from the Gulf, streaked with blood, to your tall, proud mountains, rabid dogs rave

Iran, my land, look how the ugly hyenas plough clots of blood in your rich soil, look how the clear water from your depths, is sucked into the sewage that is imperialism,

But, Iran, my land, I vow, I vow to answer, the silence of your night, with the clamour of bullets; the darkness of your night, with the flame of bullets; and the cold of your night….

Table of Contents

Introduction by The Organisation of Iranian People’s Fadaee Guerrillas

CHAPTER 1

ARMED‑STRUGGLE IN IRAN: THE BEGINNING

The Enemy’s Efforts to Capture Comrade Behrouz & Me

CHAPTER 2

ARREST, TORTURE, INTERROGATION

Torture in the Police Detention Center

Mercenaries Panic in Facing Armed Struggle

More Interrogation, More Torture

The Torture & Martyrdom of Comrade Behrouz Dehghani

General Samadian‑Pour: Chief Hoodlum

A Meeting with Comrade Hamid Tavakkoli

A Meeting with Comrade Ali‑Reza Nabdel

The Kindness of Torturers: Another Trap

Victims of Poverty & Ignorance

Comrade! Think of Flying, Birds are Mortal

Faith & Will‑Power Will Triumph Over Torture

The Duty of Every Revolutionary in the Prison

The Introduction By the Organization Of The Iranian People’s Fadaee Guerrillas

The armed struggle for the liberation of the people of Iran, undertaken with a full understanding of the historic currents of the present era and based on an objective analysis of these currents, has put us in the forefront of world revolution.

Our age is the age of liberation of the enslaved masses exploited by imperialism. It is the age of peoples’ liberation movements. Everyday the masses of the world open up a new front against world imperialism, and everyday a new blow is inflicted on imperialists.

Now the masses have risen, in Asia, in Africa, in Latin America, and the invigorating sound of machine guns, the clamour of the liberation movements can be heard throughout the world. Faced with the historic uprising of the oppressed masses, the bloodthirsty imperialists and their reactionary stooges will not lay down their slaughter axe. Desperately they try to destroy the armed pioneers of the peoples’ revolution and to block the path of the power of the masses ‑ a destructive historical flood, which will demolish the castles they have built on misery. The enemy does not stop at any crime. However, death is no longer the answer. Now the wish of Comrade Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, the heroic son of the peoples of three continents, has come true. Now when a warrior is slain in the front against imperialism, many fighting hands reach for his weapon to continue the solemn struggle, which leads to the freedom of the masses. This historic development inevitably claims many martyrs, but that does not deter the revolutionaries. Rather, it makes them more determined.

The guerrilla movement in our country has arisen out of both objective and subjective conditions and phenomena. The deepening hatred of the people for world imperialism and internal reaction, the rule in Iran of the comprador‑bourgeoisie and the intense and systematic political and economic exploitation of our masses coupled with imperialist deculturalisation of the country; the failure of the regime’s ‘reforms’ which aimed to reduce the revolutionary potential of the Iranian masses; the phenomenal political suppression in Iran which has made any kind of open or semi‑overt struggle by the masses impossible, together with past experiences which had shown ‘peaceful’ opposition to be vulnerable and sterile; the impact of the revolutionary movements of the Third World in general and of the Middle East in particular; increasing political and historical consciousness of the young generation in Iran; and, study and analysis of former methods of resistance and struggle by those who pioneered the armed revolution; these were all among the basic elements that brought about the armed guerrilla movement in Iran.

Before the advent of armed struggle in our country, there existed a few revolutionaries who were able to perceive the bright horizon of the future while submerged in the darkness of the Iranian political scene. It was these people who set the wheels of armed revolution in motion. The armed struggle in Iran started at a time when the enemy imagined itself more powerful than ever, and the imperialists were triumphantly boasting about “this island of stability and calm”. It was a time when the many politically blind were revealing their ignorance of the fermenting currents within Iranian society with their well known saying: “Nothing can be done in Iran at present”. These subjective dogmatists, isolated from the Iranian society and its realities and unable to offer a clear and realistic course of action to break the political deadlock in Iran, were borrowing page after page from the book of another country’s successful revolution, prescribing duplication of set patterns out of line with the particular realities of our country, clinging to their dogmas and refusing to learn from their mistakes. It was a time when the opportunists were ‘awaiting favourable circumstances’ when the masses would all rise together as if in a fairy tale of a revolution. Meanwhile, they were accepting a degrading and sterile life under the venal Shah, living a corrupting life in silence and inaction, pretending to be part of some imaginary undercurrents that would suddenly surface ‑ undercurrents that did not and could not exist as imperialism and reaction, with their thousands of schemes and conspiracies, stopped its growth and ended its very existence.

It was under these conditions, with painful memories of past defeats casting a dark shadow on the minds of the people, with the blind hopes and the cold hearts that the young generation of our land rose to its feet. A young generation had achieved a level of political, intellectual and practical maturity to be able to undertake its historic mission. A young generation that was emerging from the darkness, with a firm belief and a revolutionary dedication, to raise the arms of revolution and open the way for the struggle of the oppressed masses.

The young generation in Iran has risen to wipe out the degradation of the past two decades; to wipe out the gloom and the doubts; to break the silence, the suppression; to end the, impotence; to condemn looking abroad for all inspiration and patterns of action; to eliminate the sewage of opportunism; to destroy the yoke of imperialism and reaction, and to accomplish the rule of the people in their homeland.

This heroic young generation set to work without any external source of support. It stepped out on the road to revolution without the benefit of any practical experience and unable to draw on the experience of previous generations, as no positive and creative experience had been left behind. The work had to start from the very beginning.

The experiences of the past generations could only teach the young how a struggle that fails to arouse the masses and rely on them is doomed; how political servitude and the lack of an independent line compatible with the particular conditions prevalent in Iran can leave the movement subordinate to the interests and compromises of others. The experiences of past generations taught the young that lack of a realistic political unity among the people’s forces against the common enemy leads to inefficacy and disintegration; that indecision and lack of courage and determination leaves the country to the whims of the enemy; that lack of progressive and truly revolutionary Organisation and leadership, hardened in the field of battle and not arising out of political play‑acting and show business, can waste the tremendous potentials of the masses and lead to impotence and defeat, in spite of the fortitude and sacrifices of many children of the masses.

This was how the young generation of our country undertook the grave responsibility of cleaning up the sty of the Iranian political scene and laying the foundations of people’s revolution.

In the beginning, their hands were empty but their hearts were full of hope and determination. The movement grew in the course of revolutionary action, under the darkest tyranny, in fire and blood. This generation has had to build from the very foundations, without any support but that of the masses. It had to create everything, and so learned to be creative, constructive. This generation has given all, dedicated all, to gain all for the people. This generation has solemnly accepted its historic mission, has courageously faced difficulties, and emerged victorious, has terrified the Shah, his masters and his terrorists.

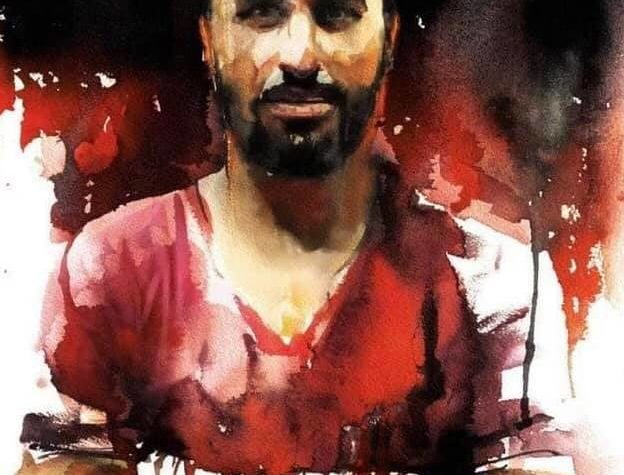

Comrade Ashraf Dehghani belongs to this generation. Comrade Ashraf was arrested (in the Spring of 1971) while on a mission. She was subjected to barbarous tortures by the fascist regime but, with her revolutionary determination and fortitude, she endured it all and revealed nothing after many months of torture, Comrade Ashraf was tried and sentenced to ten years imprisonment. In March 1973 she escaped from the Shah’s prison and rejoined the ranks of the O.I.P.F.G. Now together with her comrades, she continues the war.

Comrade Ashraf Dehghani’s fortitude and her resistance in the face of the regime’s mercenaries, the agents of imperialism in Iran, has not been an exception to the rule. Countless revolutionaries, children of our people, have shown indomitable firmness and resistance under the savage tortures of the fascist regime and its North American masters. There have been, and there remain, countless heroes of the Iranian Revolution. There have been countless martyrs. We are now able to tell the masses of Iran, to tell the World, of her heroic resistance as an example of the courage and determination of the Iranian revolutionaries.

With unwavering belief in our final victory

The organisation of Iranian People’s Fadaee Guerrillas

Chapter 1

Armed Struggle in Iran: The Beginning

The End of Silence

In Bahman of 1349 (February 1971) the Battle of Siahkal opened a new, significant and decisive page in the history of the struggle of the Iranian people. For imperialism and reaction in Iran, the bell began to toll.

The brave children of the nation had risen to fulfil their historic mission, breaking the silence of many years, to shatter the enemy’s myth of invincibility, to raise the tremendous force of the masses and open the way to freedom from oppression, suffering, deprivation.

In the space of four months after Siahkal, many police stations were successfully raided and many banks expropriated. Preparation was successful, although inexperience had taken toll and many revolutionaries were captured by the regime and summarily murdered by firing squad. More action followed, and much more was to come.

After the trial of the murderous traitor, General Farsiou (1) in the People’s Court and his execution, the enemy, still in a state of shock, unleashed a widespread campaign of terror and intimidation. After murdering some heroes of Siahkal (2), the regime foolishly imagined that it had put paid to the movement at its birth. In its ignorance, it even believed that the fifteen heroes killed by firing squad or under torture, were the whole of the guerrilla force! When they learned of nine others, the regime, with a typical lack of understanding of Iran’s historic conditions and processes, decided that capturing these revolutionaries would, again, put an end to the armed struggle, and give the Shah a new lease of criminal existence.

The regime distributed ‘wanted’ posters with photographs of the nine throughout the country with promises of rich rewards. Newspapers told the people there were only the nine left out of the movement. The nine revolutionaries were Comrade Amir Parviz Pouyan, Javad Selahi, Hamid Ashraf, Manuchehr Bahai‑Pour, Eskandar Sadeghi‑Nezhad, Abbas Meftahi, Ahmad Zibarom, Mohammad Saffari Ashtiani and Rahmatollah PeiroNaziri). The enemy was naive enough to expect the people to betray their heroes. The only result of this action was that the masses throughout the country learned of the existence of the revolutionary forces and of the beginning of the armed struggle. The regime had thus unwittingly achieved what the revolutionary forces had tried to achieve. Nine pioneers of the people’s revolution were thus known to the people. The reaction was breathtaking. The posters ended up in people’s homes, over the mantelpieces where heroes belong. The nation was exalted. At long last, it had found hope, and it had all happened overnight. The heroes were cherished: “We would not sell them for anything”, “the money would be haram*, “these are like the Viet Cong”…

The effect on the intellectuals was also overwhelming. They took up armed struggle at an incredible rate. The revolution began in earnest, and this all helped to drive it on to its logical and historic conclusion.

Together with my revolutionary brother, Behrouz, I had joined the armed struggle at the beginning. When the enemy was leaving no stones unturned looking for the nine heroes of the people, I shared the same operational base with two of them; Comrades Pouyan and Nabdel (4). Our group was charged with reproducing and distributing leaflets and communiqués. This was our main duty, but we would undertake other tasks as the need arose.

Every revolutionary action brought new hopes and elation. The correctness of the path was not in doubt and armed guerrilla action was clearly the only way left to overthrow the rule of reaction and imperialism. However, we did not know, because of our inexperience, how long it would take to establish a wide base of support. What was in question was not the direction of the struggle, but its tempo. Comrade Pouyan’s view was: “In this struggle, the Organisation may be dealt heavy blows. There may be many casualties, but the struggle we have initiated is just, and even without the O.I.P.P.G., the fight will be continued by other revolutionary organizations”.

On 14 April, 1971, Comrades Pouyan, Golavy, Nabdel and Selahi, left the base at 6.30 p.m. to post and distribute leaflets. The former returned safely but Nabdel and Selahi did not come back. We later learned that they had been spotted posting leaflets on a wall by a retired army N.C.O. who raised the alarm. The comrades had not previously surveyed the area, and, attempting to escape, they rode their motorcycle into an alley leading to the police station in Pamenar Avenue. Station sentries opened fire and an unequal battle ensued. Comrade Nabdel was badly wounded and fell unconscious. Comrade Selahi fought on and, with his last bullet, shot himself in the back of the head, denying the enemy the opportunity of: using his death for propaganda: “One of the nine …

Comrade Nabdel was taken to the police hospital. Without attending to his injuries, the enemy began torturing him. Indeed his wounds were mauled and whipped with an electric cable. His resistance in those critical first days was astonishing. It was such that the torturers were left full of admiration! He had been told that a bullet in his leg would not be extracted if he refused to talk. His response was typical: “the bullet is yours, the secrets mine. I will keep what belongs to my people and myself”. At last, the enemy relented. He was given medical attention but interrogation went on. One day, he hurled himself out of the window of his third floor room trying to take his own life lest the enemy extract any information from him. He survived the fall, with a few broken bones and burst stitches. He had then tried to tear out his intestines but was captured.

Then he was told: “we have arrested all the members of your organisation and soon you are all going to be shot”. His reply was: “that is not important. The struggle goes on. We may be torn apart, but we shall never break, we shall never bend”. For many days, he had withstood savage tortures without revealing a word. He even resisted for twenty days before disclosing the address of the house our team had used as base. But the enemy attacked an empty house.

*Haram: unclean, profane, and religiously prohibited. (I.C.)

Errors of Inexperience

Having lost hope for Comrade Nabdel’s return, we stayed the night in the same house. The following morning we cleared the place out and burned some documents. I wont to Tabriz in the afternoon but Comrade Pouyan together with another comrade stayed for one more night. Obviously, if Comrade Nabdel had revealed the address to the enemy in the first two days, the clash of Niruye Havai Street (5) would have happened there and then. This fact was important, as every hour of the life of a revolutionary fighter, particularly one like Comrade Pouyan, is most valuable to the struggle.

Next day I warned the comrades in Tabriz of Nabdel’s arrest, but neither Comrade Behrouz nor myself went into hiding Two days later I returned to Tehran as arranged with Comrade Pouyan, but failing to meet him, I went to Tabriz yet a second time. Those trips were a mistake for two reasons. Firstly, despite my trust in Comrade Nabdel, I should have gone into hiding following his arrest. Secondly, having told my family that I was studying in Tehran, my trips in the middle of the academic year aroused suspicion. However, this time I stayed in Tabriz for a week before returning to Tehran. Comrade Behrouz joined us in Tehran a few days later. Still, not knowing what Comrade Nabdel was going through not to reveal our identities, we were going about freely.

Each and every one of our activities immediately following Comrade Nabdel’s arrest, was an error. Inexperience, lack of objectivity, and our ignorance of the enemy’s mode of operation created many false images in our minds.

More than twenty days after the capture of Comrade Nabdel, I was instructed to contact, in a nearby mosque, the landlady of the house we had left, to learn of developments. There was also a plan to attack the SAVAK agents in the house. I went to the mosque in the evening in time for Nemaz*, as it was easier to spot her at that time. I approached her and talked to her. She was quite obviously frightened. It was plain, SAVAK agents were in the house. Nemaz started again and I slipped out.

I later learned that, after my visit, a herd of secret agents had daily accompanied her to the mosque. As if I would return there!

*Nemaz: Moslem prayer. (I.C.)

The Enemy’s Efforts To Capture Comrade Behrouz And Me

After many days of torture, and after much heroic fortitude, Comrade Nabdel disclosed the identity of Comrade Behrouz to the enemy. SAVAK agents raided our home in Tabriz in the middle of the night and ransacked the place. They made my mother stay inside, detaining whoever called at the house. Next evening my younger brother Mohammad (6) did not return home and was arrested.

The mercenaries then raided my sister’s home and arrested her husband, Comrade Kazem Saadati (7) and took him to SAVAK’s Tabriz headquarters. Kazem, one of the most progressive sympathisers of O.I.P.F.G. was living with his wife and child, and had not gone into hiding. On arrest, in order not to give any information to SAVAK, he pretended to be a naive simpleton, totally ignorant of our activities. The mercenaries released him hoping he would help them capture Comrade Behrouz, and threatened him that his lack of co‑operation would lead to re‑arrest and torture. He realised that he was under close observation, but was unable to warn Comrade Behrouz who was due to make contact with him soon. On the night of his release, he committed suicide by taking poison and cutting his wrists, so that Behrouz would be warned by the commotion. The enemy learned of Kazem’s action and did everything possible to save his life. He was taken to hospital, and it was demanded that his life be saved! However, Comrade Kazem, his secrets buried in his heart, joined the martyrs of the Iranian Revolution. The enemy frustrated and dejected, became an object of ridicule by prosecuting, supposedly on behalf of Kazem’s family, the intern who had failed to save his life! To the embarrassment of SAVAK, the people of Tabriz in great numbers gloriously honoured their hero and gave him a most splendid funeral. To disrupt the funeral would have been an admission of guilt by SAVAK. Instead, the enemy later retaliated by arresting those who had been most outraged.

Comrade Kazem had once again proved the regime’s impotence and inefficacy in the face of revolutionary determination and absolute dedication. His last words to my mother were: “the enemy may murder your children under severe torture, but do not ever plead, do not ever beg. The enemy is too base for that”.

The elaborate efforts for our arrest even extended to setting up roadblocks on all routes out of Tehran. All the universities and other institutes where I could have been studying (that was what I had told my family) were probed.

In one instance, a shrew of a woman, probably the same one who later acted as my jailer, went to the dormitory of a girls’ boarding school at 2 a.m. With the building surrounded, the woman awakened the students one by one, introducing herself now as my aunt, now as my sister‑in‑law, asking their names, telling them my mother was gravely ill, and she had come to take me to her. Having noticed her varying identity, the students began asking questions and a group of them were ready to throw her out, forcing her to abandon her search and run to safety. Yet another unsuccessful ploy! The only result of these midnight raids was that groups of students were made more aware of the regime’s nature and given a glimpse of the enemy’s stupidity and brutality.

Chapter 2

Arrest, Torture, Interrogation.

My Arrest

After the blow, we reorganised and resumed revolutionary activity. In the morning of 13 May 1971, I left the base with Comrade Behrouz, to continue surveillance of an enemy mercenary. I was standing on 21 AzarStreet when two cars screeched to a halt in front of me and a group of men charged out. The first one to reach me put one hand over my mouth and, uttering obscenities, tried to lift me up and carry me to one of the cars. Soon the others joined in. Their loathsome faces and their foul language worthy only of the Shah’s police and SAVAK thugs, left me in no doubt as to their identity. What was not clear was how they had identified me, and how much they knew about me. I refrained from expressing my feelings about them and the regime they represented, in case they had taken me for someone else. Yet I could not and did not want to submit sheepishly. I felt it my duty to unmask the Shah’s louts and expose their foul nature for all to see. I started shouting and screaming to draw the attention of the people around. How wrong those mercenaries, those venal traitors of the people, were to think they could so easily drag me off. Shouting and screaming, I was defending myself, punching, kicking, and biting their hands, arms and legs. Yet more enemy agents thronged around to help arrest me quickly, and to disperse the crowd that was growing more and more numerous around us. Suddenly I knew how the enemy had recognised me. A ghastly face told me this.

Having vacated our hideout in Tehran following the arrest of Comrade Nabdel, I had occasionally stayed in the house of one of my brothers that was apolitical. There was another tenant in that house who had introduced himself as a civil servant. He had seen me a few times in my brother’s house and twice near Tehran University where I was carrying out a surveillance mission. In the raid on our home in Tabriz, SAVAK had obtained my photograph and circulated it to its agents. As it turned out, the ‘civil servant’ was one of them. At the time of my arrest, a major strike by the students had just ended and no doubt, the area was swarming with SAVAK mercenaries. I was to blame for my arrest, failing to analyse the situation and going there daily. Standing in the area seemingly aimless, day after day, I had undoubtedly attracted their attention.

When I was struggling with the Shah’s ruffians and more of them were joining in, I saw his wretched face. He must have been hiding from me, so that the enemy could feed me lies about their invincibility: “We are very powerful. We know all. We see all and some such nonsense, but he had to join in. What a ghastly face he had! The struggle went on for some fifteen minutes. My clothes were torn. I felt pain everywhere but still found great strength. Finally they managed to grasp my arms and legs, and I was dragged into the car. I was still struggling, surprised by my own strength. They could not hold me still. When unable to drag an arm or a leg free, I would bite them. One of the thugs was biting my finger as hard as he could. Another was aiming with his revolver, shouting he would shoot if I moved. What a clown! I moved more violently than before and knocked his revolver out of his hand. The bravos had panicked, scrambling to get it out of my reach. I pulled one leg free and kicked the rear window, breaking it. They grabbed me tight. I could only move my head. Raising it, I saw a bus. As usual it was packed. Tired faces were looking out of the windows. The bus was undoubtedly from the south of the city, from the slums. I thought to myself: these are the last proletarians I shall ever see. They had not noticed me but I shook my head to them, trying to tell them that I shall love them forever, that I will never turn my back on them….

The thought that I had been captured so soon, without having done anything for the revolution, made me feel ashamed. I thought: at least now, I must carry out my duty well under torture.

Torture In the Police Detention Centre

The car stopped at the Police Intelligence Department. I was dragged out of the car and into the building. I was shouting and struggling. Some pulling and others shoving, they made me run the length of a long corridor. They kicked me in the back. I fell on my face. They forced me up again and the marathon continued. Thus, we got to an ‘interrogation’ room.

They started “…(obscenities)…”Where is Amu-Oghli? (nom de guerre of Comrade Javad Selahi)(8) Did you see what we did to Farhoudi? (9) How many bastards did you abort? * Where is your phony uncle Pouyan? One of them held a photograph in front of me taken while I was in high schools crying; “See who this is”. Then I saw the back of the photograph: “She is wearing such and such a coat”. I looked at my coat. It was clear. They had been to our house, and what they said indicated the extent of their information. There was no longer any point in hiding my feelings. My hatred. The hatred of them and the class they served: “Death to you! You base criminals…enemies of the masses, dirty leeches, drinking the blood of the workers….” Then some poems that gave me strength:

“With each squeak,

The fact is revealed,

The aging machine shall run down to ruin”

“Fight we must,

Like the Bolsheviks

What is to our hearts,

Burning in flames,

Shooting by the foe?”

They attacked. Punching, slapping, kicking and passing me from one to another. What was left of my clothes was now torn in pieces. Beatings went on. After a while “Khatayi” the ‘Head of Operational of the Police Intelligence Department’, said to be a close and favoured underling of the Shah, walked in shoving others aside: “What is this? Can’t you treat people with respect? What do you want of her? Her address? That is not important. It can be asked without beating and shouting”.

In the past, Behrouz and his comrades had often been taken to SAVAK. I had heard of their treatment and was somewhat familiar with the enemy’s techniques, brutalities, fooled by words of kindness and concern. His warm face and his calm and polite tone did not fool me to change my attitude toward him. He was an enemy, mean as the other mercenaries, hiding his ugly criminal face behind a mask of humanity! He went on: “Tell us the address. We wish you well. The sooner your friends are arrested the better it is for them. Because they commit fewer crimes. Isn’t it a shame that so many good and well educated young people should die?”

Looking at the ghastly beast, seeing thorough his transparent duplicity made my blood boil. I cut short his speech: “You enemy of the human race, I shall never compromise, I will fight to the end….” His ‘kind and gentle’ face went sour. Now it reflected his true self:

“Then get the hell out of this… (more of their obscene vocabulary)….”

The thugs strapped me to a bed. The room was packed with them. They had all come to watch. They presumably found the torture of a revolutionary girl interesting. Some looked calm and composed. I found that strange. I had never imagined a torturer could be so indifferent. As if to them, it all seemed routine. The main torturer was Captain Niktab. Others helped him. They were whipping the soles of my feet. It was unbearably painful, but chanting slogans and singing gave me strength. The words made them angry. They would whip harder. Naming the Shah and calling him what he is, particularly angered them; or they have to pretend that it did. Whipping went on. Stroke after stroke. Now all their faces began to twist, A few came close: “Have mercy on yourself. Tell everything”. Their expression of concern came simultaneously with the strokes of the whip, so that while feeling pain one would also see the way out! It seemed a good opportunity for playing games with them:

“How can I tell you the address when I am taken there blindfolded?

How can I tell you an address I do not know?”

They saw signs of resignation. Whipping stopped:

“Alright, which area was it in?”

“I don’t know”

“What colour was the door? Was it an apartment? Facing, north or south?”

“I don’t know, My eyes were always shut”.

“I will now open your eyes” Khatayi said sarcastically and took over the whip. The ‘kind‑hearted’ few started again “Have mercy on yourself….”

The pain was unbearably intense now. I needed a breathing apace to think, to gather my strength, to build up my will power. I said, “the name of the main road was Khani Abad“. They smiled in triumph: “What was the name of the side road?” “I don’t know…” The strokes began to land again. Until I could concoct a fake address, whipping stopped and restarted a few times. Another advantage was that they were convinced that I did not want to disclose any information, but that I could not endure the pain. With the ‘address’ complete, I was unstrapped and told to walk. It felt strange, as if thousands of pins were piercing my body. I could not walk, could not sit, and could not stay still. They grasped me and walked me the length of the room. Then a woman came and bandaged my feet. They had thought the address genuine. Their attitude was different now, trying to get more information softly. My behaviour must have seemed inconsistent. While my resistance had supposedly crumbled and they had obtained the address, I was so saturated with hatred that it was impossible for me to look at any of those criminals without describing his true nature, his hideous inhumanity.

I noticed a man sitting in a chair, looking pale, petrified, his eyes wandering aimlessly. He obviously did not look like a SAVAK thug or police, more like a stunned, involuntary onlooker, one forced to watch a horror film and deeply shaken by it. I did not dwell on him then. Later I learned that, passing by at the time of my arrest, he had been so outraged by the savagery of the Shah’s ruffians, that he had attacked them, injuring one. He had the attempted to escape but the mercenaries had given chase and arrested him, firing warning shots.

A herd of mercenaries had gone on a wild goose chase to the address I had given them. I felt quite pleased, having sent them across the city making fools of them, and gaining valuable time for myself to think. Later on, however, I regretted that manoeuvre, because the police kept vigil in the area. Perhaps some comrades did live there. Perhaps I had unwittingly led the enemy to some revolutionaries. In fact, I had not, but the idea was a mistake.

I could not feel my legs. They were totally numb. Dumped on the floor, it was very difficult to move. It was about noon. A man came in with two plates of food, spoons and forks. One plate was for a uniformed pig sitting behind a desk in the room, the other was for another next door. He paused, asked me if I wanted lunch. An idea occurred to me. I accepted the food.

The plate was put in front of me. At first, the officer watched on, I started eating. He turned his attention to the food. That was ample opportunity. I sat up straight and rammed the fork into my throat, trying to thrust it in as far as possible. I thought this would kill me, I tried and tried but no use. The officer jumped on me, grabbed the fork. Swearing, he started to punch and kick. Then the other thugs burst through the door. They had received word the address was false. They were not amused.

Torture started again. This time they gave me electric shocks using truncheon‑shaped electrode. Before going on to use the shock to inflict pain, they were using the electrode to humiliate me, the target was the morale rather than the physique. They had completely undressed me and, uttering revolting obscenities and sick ‘jokes’ that at worst reflected their state of mind, set about administering shocks to the sensitive parts of my body….

That filthy beast, Niktab, walked into the room. He looked dejected, downtrodden and miserable. “How can anybody descend to such extremes of nothingness, of wretchedness?” I wondered. My attitude was wrong. How could it be otherwise? In the class society, a person without a class base is an object, a meaningless, worthless venal object.

The embodiment of misery, the manifestation of defeat, he cried: “So you wanted to rob banks, ha? We’ve caught you all….” That day a bank in ‘Eisenhower‘ Street** in central Tehran was to be expropriated. I could read the result in the animal’s twisted face. The comrades had carried out the mission successfully. No one was arrested.

He strapped me to a bench, face down. The shameless vermin dropped his trousers and assaulted me. Would they stop at nothing? They wanted to degrade me, shatter my nerves, overcome my resolve. I was infuriated, seeing blood before my eyes. But no, I had to try to keep calm so that they would feel the shame and degradation instead. I wanted them to know that their degenerate and shameless barbarity did not affect me, was unimportant to me. Why should it be otherwise? To me, what was the difference between this and being whipped; they were both tortures. They were both being carried out with the same aim. The evil aim of extracting my secrets, the people’s secrets. And I would endure both for a worthy aim. To further my glorious cause, I had to keep the secrets in the interest of the struggle, of the revolution. For me the torture, the degradation was short‑lived and would pass. I thought of the toiling masses who endured it not for an hour, not for a day, but every moment of the suffering that is their life. The retarded vegetable who had expected to enjoy watching me struggle and suffer had failed again.

Once more, I was strapped to the bed and whipping resumed. This time, with the whip landing on the earlier wounds, the pain was more intense. Relying on my will power, I tried to overcome the pain and imagine myself as an onlooker, as if watching another’s torture. I succeeded to some extent, yet the whip was a material fact, which could not be endured in this way. I needed a reality to turn my mind to. Every time the pain increased, I would call Eypak, Reihan, Robab, and Kasem…. These were some of the workers in the village where I had taught. It was as if I could see their anxious eyes watching me, as if I could touch them. They were anxious, impatiently waiting to learn of my love for them. Would I remain faithful? I could see in their kind eyes what they rightly expected of me. I could see in their kind eyes the anxiety lest I who had closely witnessed their sufferings and pains, and who had joined in the struggle to free them from centuries of slavery, would now compromise with their class enemy who had inflicted so much pain on them for so long.

I could see Eypak‘s hand, deeply cut with a sickle, yet not nursed because the work had to go on. I would think of the acute backache that plagued Robab and Reihan. Yet, they had to irrigate their tiny piece of barren land with their hands. I had before my eyes the sufferings of Golnar, the tears of Zahra, the sincerity of Ghorban, the innocence and childish happiness of Marzan who would run to me shouting “Aunt Ashraf” in the rags that were her clothes. I could remember that every time watching her unwitting joy, I would think of the agony and humiliation waiting to swamp her, to degrade her and to ruin her life. I could remember how my heart bursting with sorrow and choking with hatred of those who bring about so much misery, I would smile at her, caress her, and vow in my heart; “I shall fight for your freedom and that of all those others like you, chained by the oppressors”. Now I could see their anxious faces before my eyes. With every stroke of the whip, I would call their names. I was trying to assure them, in fact to assure myself, that I would keep my pledge.

How wrong were those torturous mercenaries who thought I was revealing the names of my comrades in the armed struggle. How unfounded was their joy. “Who else? What are their family names?”

At last, they were tired of whipping. They tried a stupid manoeuvre. Khatayi aimed his revolver and threatened to shoot through my nose. He was some four meters away. I believed him at first. Just when he pretended he is pulling the trigger, I moved my head forward in the path of the bullet. They laughed mockingly. The hoodlum aimed again. Once again, I moved my head to line up the bullet. Pretending he was angry, Khatayishouted; “Don’t move, I only want to make a hole in your nose”. I realised this was their idea of fun! They only wanted to threaten, and more than that to mock me. I stopped paying attention. The game was repeated three or four times, changing the revolver or the distance. Were they hoping to break my resistance with such clownish acts? How very naive!

They took me back to the wooden bench. Lying me on the back they passed my arms down the sides and handcuffed me under the bench. Then they all walked out. The bones in my back were pressed tightly against the wood. I felt as if a big hole was gaping in my back. The pain was intense. It seemed more than the pain from the whip. There were no torturers around to shout at to take my mind off the pain. I started reciting a poem by Comrade Mao. The poem ended but not the pain. My arms were so stretched I felt they were being torn off. The piercing pain of the wounds on my back was burning through my body. I could not rest. I wanted the pain to go away. That feeling was new and unwelcome. I reproached myself. This shows that in the past I had failed to get myself used to pain and suffering.

The ugly face of a mercenary appealed through the door. They came in one at a time, tried to persuade as to go along with them, and left in despair. one would talk of my mother’s sorrow, another would utter: “To hell with the masses and all the barefoot and poor. You should think of yourself”! Others would promise me money and trips abroad!

Apparently, there was a prize for anyone who could extract any information. One thug leaving disappointed, groaned: “You could have talked and made me a little money”!

I do not know how time went by. Perhaps I had passed out, or perhaps I had fallen asleep. When I came round, they were threatening: “You think this is it? This is nothing. We are not SAVAK men. When you go to Evin and face the SAVAK people, you couldn’t possibly keep silent. It is dreadful in there. We are taking you there tonight”.

A horrifying picture of SAVAK and torturers had been in my mind before. While telling them “it does not make any difference, you are all the same”, I thought these police torturers must be novices compared to the animals in SAVAK. Yet, my resolve to preserve the secrets of my comrades, and not to surrender to the enemy, remained indomitable.

*The regime’s propaganda machine accuses revolutionaries of sexual perversion, addiction to drugs, etc., so familiar to its leaders.

**The puppet ‘honours’ his masters. (I.C.)

In Evin Torture Chambers

It was night time. Niktab and a few others came to take me to Evin. They had a large prison coat for me to wear. Every time one of them came close, I kicked. At last they all grasped my arms and legs and put the coat on me as I struggled. Then I was blindfolded, carried outside and dumped on the floor of a car. They sat on the seats, holding me down with their feet, kicking all the time. That filthy beast, Niktab, put my neck on his knee, pressing my head down every time I tried to move. Thus, we left the Police Intelligence Department for the Evin torture chambers.

On the way, I thought of a Brazilian comrade who had bitten his own tongue off in order not to talk. I tried to do the same, unsuccessfully. Of course, I was not firm enough in my decision, reasoning that if one wants to disclose anything, it is always possible to write it down.

In Evin, they dumped me on a bed. Looking through the blindfold, I could see vague figures of the ‘expert’ torturers. Among them, was the large gorilla‑like mass of Hosseini. “Where have you taken me?” I asked, “Who are these?” It was Sabeti answering, trying hard to sound impressive: “These are my slaves. I have cut off this one’s ear”, and, patting the gorilla’s chest: “and I have cut off this one’s tongue…. this is my land of….” I do not remember what he said. Something witless like; land of strange, bloodthirsty beasts. Then

they measured my height! I felt totally relaxed, in high spirits. There was no fear, no worries.

After their silly japes, they started naming some people, asking me which ones I knew. I was trying not to hear any of the names for fear of reacting to the name of a comrade.

Then they asked where my hideout was. I repeated the faked address. They removed the blindfold and took me to a large room with a bed and two wooden tables.

First Hosseini, twisting his face, grabbed my head shaking and turning it violently, howling like a wild boar. His cries were deafening. He was trying to frighten me. Niktab, Hossein Zadeh, Javan and a few other mercenaries whose names I do not know, burst into the room swearing “Where is this….” Hossein Zadeh shoved others aside, sat on the bed holding my body shaking me, uttering: “Look into my eyes, darling, into my eyes”. I would look down, or around, I did not want to pay him any attention. He was furious, shouting, jerking me, repeating “into my eyes….” What did the criminal savage want of me? What did he expect? Perhaps he thought he could hypnotise me. Gradually he got bored and told one of the underlings to get the whip. Turning to me he said: “Do you know me? I am Hossein Zadeh, the famous torturer, executioner”. So they even take pride at that! Pulling his ghastly face, he would growl: “This is Evin, and I am the expert torturer”. He was truly the embodiment of ugliness. They seemed so stupid, so detestable, but were not frightening. The realisation that I was not at all frightened filled me with joy.

They threw me on the floor, tied my hands to the bed. A few of them grabbed my legs and ankles, pulling me away from the bed. Hossein Zadeh started whipping my legs, others would kick me and swear: “Come on you…. let’s have it out….” Javan and two old Turkish men who looked almost identical and quite ridiculous, were doing the soft talk: “Come on girl, don’t hurt yourself needlessly, talk”.

My silence was driving Hossein Zadeh insane. He looked wilder with every stroke, he did not seem to know quite what to do. Whipping harder and harder, he would howl louder, scream and swear…. Finally, he got tired and stopped. They untied me and told me to walk. My legs collapsed underneath me. They were shoving me in the back, forcing me to walk. The two old men were going on:

“Come on, tell them what they want to know. Your comrades have certainly left the house by now. You don’t know how clever these agents are. Another day or two, and everybody will be arrested. They might even kill your friends. You must also think of others, isn’t it a shame for those young people to get killed? Never mind about them, what have their parents done to deserve losing their beloved children? You know yourself this sort of thing can only lead to death. But if you help, we can arrest them, and make them see sense. We promise not to torture them. We know you have been misled”!

Their stupidity was quite hilarious really. Did they actually expect anybody to believe that nonsense? I wanted to pass the time somehow to lessen it. Saying a few words now and then, I would pretend that I was about to answer their questions, as if I was making a decision: “No, its no use…. what can I say?….no, I shouldn’t”. The old couple would insist: “No, you must, it’ll be good, it’ll be useful”. My pretence of indecision went on. Hossein Zadeh was frustrated, shouting: “If you don’t, I’ll get the hell out of you with this whip, again and again”. I was ignoring him, listening to the old men, saying “But you don’t believe me. I told you it is KhaniAbed Street…. no, no, why should I tell you…?” I had repeated the false address in my mind so often now that I was beginning to believe it myself. It took a long time for me to complete the address. They seemed angry and bored.

I was tied to the bed again. They had brought in a thick, large stick, all mocking me and uttering obscenities. The traitor mercenary, Hossein Zadeh, was glaring at me furiously, insanity written on his face. He was a mad criminal and he looked like one. But, beneath, one could see nothing but helplessness and impotence. He was holding the stick, growling: “This’ll take care of you. Just wait and see what tortures we have in store for you…. We’ll stick this up your….”

I was burning with hatred. It was very hard to remain silent. I knew that any reaction from me, shouting and swearing* would only give them perverse pleasure. When tormenting a victim particularly when this involves the victim’s private parts, they expect cries of anguish and indignation. I wished my hands were free to strangle them all. Being tied up, helpless, was most frustrating. Those filthy mercenaries who tremble when faced with a revolutionary guerrilla, were now displaying bravery against a powerless fighter in chains. What admirable courage! They would lift my legs with the stick, rushing from all directions, taunting, harassing me … I could only retaliate against their utmost shameless, impudent insolence with eyes saturated with hate.

At last they put the stick aside. Now Niktab picked up the whip. I was looking at his face, a ghastly face, drenched with crime. He was a venal object, a base mercenary serving the enemy of the masses. The masses I truly loved….the masses whose pain I had witnessed and every time bitter tears of hatred of the enemy, had run down my face. Were those feelings shallow? Superficial? No. I had dedicated my life to the cause of the masses, and this was a meagre price to pay for such a glorious cause. I remembered that in the past, before reading a pamphlet, I would think of the difficulties that lay ahead if one were to take action, and would tell myself, if you are prepared to face the difficulties, go ahead and read; otherwise, it is the height of dishonesty to read simply for the satisfaction of intellectual curiosity.

And now, faced with those difficulties, with this terror, it would be the height of dishonesty to forget the cause. To me, a spoken commitment to the cause, without action, and without being prepared to endure pain and torture has always been and will remain, abhorrent and revolting.

Thinking about the nature of torture infuriated me. I thought about the cause of all this savagery. The traitor, the mercenary, the servant and puppet of U.S. imperialism, does not stop at any crime to buy more time for his tyranny; and now, what did he want of me? To help him keep the people in chains even longer? To what would the disclosure of our secrets lead? Would it not enable the treacherous enemy to deal a blow against the movement? It would. By talking to the enemy, I would be serving the despotism of the Shah, even if only for one moment. But every moment in the existence of a revolutionary must be spent in the service of the revolution, the proletarian revolution. The enemy impudently wanted me to talk, to reveal, so that it could survive even longer and torture even more. Could I justify that? Never.

With every stroke of the whip, Niktab howled “Address, address”. The pain grew more excruciating; more and more difficult to endure. There were moments when I really wanted the whipping to stop. I did not want to aggravate him further with swearing at him. There was no way out of the agony. I really felt that. There was nothing I could do.

I was like a mother delivering a baby. The pain is there and goes on. Nothing can be done but wait for the birth of the child. And in that situation, the birth of the child was the arrival of death. I had to wait for that.

Gradually their repulsive faces filled with dismay. Looking at them, my confidence soared. They looked more and more bereaved. What else were the poor, feeble beasts to do? The worst and most important thing they had to offer was torture, and they had seen it fail miserably. The whipping stopped. They picked up a pair of tongs, gripping and twisting my flesh. Then they began compressing my fingers in a vice. They said they were going to pull out my nails, but they did not do that. Perhaps they did not want to leave any permanent proof of their crimes. They were helpless, frustrated, infuriated. They seemed to be exerting more pressure on their teeth than on my fingers. Other tortures were painful, but not as painful as the whipping. In between other barbarities, they would also whip me. They had lost their rhythm, seemed to have forgotten the order. Their hateful and cretin faces were covered with despair. I can still remember Hosseini, his face twitching with nervous tension, trying to thrust the tongs into my flesh and then compressing it with all his gorilla strength. Dejected, they were desperately looking for a weak point.

They brought in a box full of snakes. Some were expressing horror, cowering: “Oh, I can’t even look at the box!” They were uttering a lot of nonsense, trying to make frightening, horrifying creatures out of snakes. They opened the top of the box a little, themselves taking refuge in a corner of the room. They were frightened lest the snakes rushed out! One mercenary opened the box a little wider with a long stick. A snake crept out and under a table. They were all running around the room in panic. It was a distasteful show with incompetent actors. I was looking at them. Filthy beasts that had the appearance of human beings, but there the similarity ended. They were lacking in the most elementary human values. Their very existence infected the Earth. This was the lowest ebb in human decadence and degeneration.

Finally, one of them who had opened the box and who called himself a snake‑charmer, picked up a snake and brought it close to my head. The snake coiled round my neck. Had I not analysed their motive and mentality, I would have been surprised at their idiocy. The point was quite simple. The snakes were either poisonous, in which case they would kill me, an end I longed for and had tried to achieve; or they were harmless, in which case there was nothing to fear. Yet, they expected me to be frightened for they could only imagine ‘women’ as weak and cowardly. Their mentality is a product of their base and ignorant lives. They had indeed found ‘women’ weak, but had never been able to analyse the reasons for this. The ‘woman’ in their mind is indeed weak. She has throughout the centuries, in class societies and in the reproduction process, suffered twice: once together with a man, she has been exploited, humiliated. Her energies have been wasted. She has been ‘enjoyed’… and once again she has suffered the same from a man.

But when a woman attains class consciousness, and together with a man who has also regained class consciousness, an awareness and understanding that leads them to uproot the corrupt class structure, then she is no longer the ‘woman’ of reactionary standards and values but a “human being”. She helps to build a structure, a society, in which human beings regain their just and glorious place. To that end, she steps on the path to freedom, freedom for all. She helps to build a society in which the question ‑ how much freedom for women is irrelevant- a society in which all human beings, men and women, have attained true freedom, and for the progress of which, women and men work side by side.

How could these mercenaries, understand this glorious reality? They could not and I did not expect them to.

Once again, they had failed. The snakes crawled over my body while I was sitting, coolly, telling them “So what? Do you really expect me to be frightened?” Then I realised how painless a torture this was and started pretending that while not horrified, I did find it unpleasant, so that this particular stunt would be prolonged. While they were laughing and mocking, it was easy to see that their laughs were artificial, that they were not enjoying themselves. They had faced failure yet again.

They began talking about “enema with boiling water, tormenting pain, unbearable suffering, shoving a bottle up your…” and that: “So far we have done nothing. It has been child’s play, but the bottles of boiling water? No one has ever been able to endure that. What this wretch needs is the bottle…. Will you talk or do we have to get the bottle? …” Then the farce started with Hossein Zadeh and Niktab, laying the ‘hard’, and Javan and the two old men playing the ‘kind and soft’, and the others looking on. The old men said they were so upset they wanted to commit suicide! Pleading: “Oh no, Mr. Doctor, Mr. Engineer**, for God’s sake don’t do that, how can this poor girl bear all that pain and discomfort? She is going to die… it makes our hearts bleed….” Javan was not so good at his role, rather inconsistent, switching between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’. Some of the bravos went to get the bottles. Javan, now playing the concerned, was offering ‘expert advice’ (!):

“You know, I myself respect your beliefs. I am not saying I am a Communist (!) but I so a disciple of (Imam) Ali. Some evenings we get together and discuss Ali‘s teachings. We also believe that poverty must be erased. Why should there be so many poor and hungry in a society? But, well, there’s a way of doing everything and nothing changes suddenly. The way you are following is wrong. First, the People must be taught to defend their rights. They must be educated, cultured….”

To remind me of what was to come, one of the thugs opened the door shouting: “What happened to the bottles? Is the water not boiling yet?” The old couple were trying to look as if in agony: “For God’s sake, tell them, have mercy on yourself. Don’t let them do that to you, these rogues (pointing to their partners‑in‑crime) are truly outrageous. Honestly we can’t take it, our honour does not allow us to tolerate that sort of thing.…”Javan, angry and in despair, simply said to them: “What are you talking about! This girl’s whole being is dedicated to their organisation”. The poor beast did not know how much strength this gave me. I felt very proud.

The bottles were brought in. The old couple left the room so that their ‘hearts’ would not bleed and their ‘honour’ would not get in the way of others. Of course on the occasions that they play the ‘hard’ characters for other comrades, they leave their ‘hearts’ and ‘honour’ at home!

I was strapped to the bed face down. They kept bringing the bottles closer then pulling them back, talking about the pain and threatening to use the bottles and the boiling water. Then they carried out their threat. I did not react. At last, they gave up in despair. It was morning now. They untied me a and as an epilogue, set about slapping, punching and kicking me This was not to make me talk, I felt, but to make them feel better. Walking away, Hossein Zadeh muttered: “Tonight I hated myself”.

Perhaps their demented chief, the puppet ‘Shah of Shahs, had ordered them not to murder a woman under torture for the time being. I did not think this was the end of this torture session. I felt a burning, agonising pain, thinking my death is at last near. I was surprised to be still alive, wondering why. I was sure the torturers would come back soon, thinking to myself: this time it is certain death. One more hour. At most one more hour to suffer….

I cannot remember what happened next. I had passed out.

*By swearing at them, here and elsewhere in this book I mean describing their true nature and their role in society.

*The thugs are fond of titles. The Shah holds many ‘honorary’ degrees. (I.C)

Mercenaries Panic In Facing Armed Struggle

When I regained consciousness, I was being carried on a policeman’s shoulders in front of the Police Detention Center. As I began struggling to free myself, others grabbed my arms and legs. My head was free and I succeeded in biting the policeman’s ear. There was some commotion, somebody grasped my head. I passed out again.

Next time, coming round I found my hands tied to a bed. They had put a large open shirt on me that did not cover my body. Two policemen were flanking the bed, with a police officer* and two women were also in the room. Five people were guarding a harmless, tortured prisoner lying half-dead, unable to move and with hands bound! This is typical and indicative of the enemy’s panic and weakness in the face of armed struggle. I had done nothing to cause so much alarm and fear. They only knew that I belonged to an organisation determined to destroy the despotic regime and its mercenaries; an organisation that had successfully executed their chief thug; an organisation not held back by any fear; an organisation of devotees. How easy it was to see that what had induced so much fear in these mercenaries, what had destroyed their confidence in their regime and in themselves, is armed struggle.

They had created a powerful picture of me in their minds. I was told later that in the first few days the mercenaries of the Police Intelligence Department had been waiting in line to come in and take a look at the monster who had survived Evin without breaking. They had also speculated that I was a karate or judo expert, an untruth they had come to believe. Later, 1 heard one of the women jailers gossiping to a friend of hers, mocking an officer who, passing my bed, would keep a hand on his gun and walk a large semi‑circle not to get close!

Regaining consciousness, I first saw the two policemen sitting on either side of my bed. There was a dark hazy ring before my eyes. The policemen looked like ridiculous characters of a ‘horror’ movie. Then I saw a woman, “who is she? Is she one of the women who had many years before danced naked in front of Navab Safavi (10)?” (that is true; Safavi had apparently been very sensitive in this respect, suffering a violent nervous reaction; and the enemy had used this weakness). I swore at her, drenched with hate. The torturers had come into the room, and one of them was telling her “Don’t mind her, don’t be upset… she’s a little impolite but otherwise she is a good girl (!) … the poor girl has been misled, brainwashed you should look on her as your own child ….”

She began uttering ‘words of wisdom’. Their inept childish logic was unbearable. I decided to ridicule her, interrupting her: “I didn’t follow that”. She would explain again, I would nod in agreement from time to time. Everybody was elated: “Only a woman can tame a woman”. Then I would ask a question, forcing her to repeat most of what she had she had said. At last, she gave up.

Officers were walking in and out of the room almost constantly. I noticed that they were clumsily trying to draw my attention to their wristwatches, which they were displaying before me quite conspicuously. The two policemen in the room were trying to do the same, giving the game away and not faring much better than their superiors. They had presumably thought I was waiting for a certain hour before revealing the address, and it follows that they had put their watches forward. How feeble‑minded, how immeasurably frivolous. The whole idea was idiotic and the actors left a lot to be desired. Besides, I was determined never to divulge the information they wanted and it was not a question of hours or days.

I knew that my comrades were immediately aware of my arrest. At the time, Comrade Behrouz was not too far away and could not have failed to notice the hue and cry. Furthermore, I was due to meet some comrades shortly after the time when I was seized. They had no doubt vacated our hideout, which was, after all, a temporary base of operation. The point was not to betray even the location of the empty house, in order not to add to the fallacy of the enemy’s omnipotence, not even in the minds of the people in the immediate neighbourhood. At this stage in the struggle, one of our main duties was to shatter the regime’s myth of invincibility. The enemy must be weakened, and it must be seen to be weakened. To go against this would be an unforgivable act of treason. To me, it was unimaginable ever to turn my back on the People’s glorious cause, let alone breaking in this, my first test of dedication.

My sister‑in‑law was brought in to plead with me. She was totally in the dark regarding our activities. The enemy had raided her house and had not even allowed her children to go to school to sit for their examinations. She was broken, on her knees: “What do they want of us Ashraf? Please tell them. Tell them what they want”. “Listen”, I said, “to what is involved”, and I recited: “With the head, held up high, One must live, and with the head, held up high, one must die. To the foe, one must never submit, and one’s life, and one’s all, one must give, for the cause, for freedom, for the freedom of people”(11)

Khatayi decided it is better to take her out.

They had forced a friend to come to me with a transparent, ludicrous pack of lies; “Pouyan had attempted to kill Behrouz. He will try again. In a letter to me, Pouyan says that a disagreement has developed between them, and that he is determined to rid himself of Behrouz“! What intellectual destitution! The lie does not only reflect their impotence of mind, but also the mercenaries’ murderous, unprincipled mentality: if you disagree, murder!

The ruffians also brought two of my brothers to my bedside. They did not have much to say. My little brother’s hands were swollen and his face was bruised and scarred. The other one had also been beaten up. Perhaps the Shah’s rogues were trying to tell me that they have arrested all the members of my family, or, maybe they did not even know why they brought my brothers there!

When a friend or a relative was brought in, I would ridicule the enemy’s ‘leaders’ and ‘generals’. Pointing at the villains I would say “Look at them. These parasites can only exist if they can suck the blood of the likes of us. They can only exist if, and as long as, we allow them to. We must not let them continue their criminal life….” One of the jailers, a shrew of a woman, who was vainly trying to appear in control of the situation, would on such occasions attack me furiously, grabbing my hair, which was long, jerking my head vigorously and slapping me until my nose bled. For a while she did this every day.

That night they talked about an injection and a syrup that would make one talk involuntarily. I mocked them: “Yet another childish ploy? If one is truly determined not to talk, nothing can break one’s resolve. Still, if you have such a medicine, why did you not use it to begin with? Would you not have obtained the information sooner that way?”! The answer was typically stupid: “But it is expensive, we can’t use it for everybody”! I was, however, concerned about the possible effects of a drug, because, as a child, I used to talk in my sleep. The thought of talking under sedation was unbearable. No, I should not do that. I was trying to forget the address and the names of the few comrades known to me. I would divert my thoughts to other things. I was seriously concerned. They brought some milk, but I could hardly drink it because of the wound caused by the fork when I had rammed it in my throat.

A herd of officers had gathered around my bed, insisting that I should drink the milk. I was suspicious and, besides, their aim was to keep me alive and, at some stage, make me talk. I had to frustrate their efforts.

To me, revealing any secrets to the enemy was such an atrocious and repugnant crime, and even the thought of committing such a crime was so far from my mind, that I could not imagine for one moment talking as the enemy willed. I decided to commit suicide and rob the hoodlums of any hope of extracting the slightest information from me. Furthermore, I considered my action would be of propaganda value.

Next morning they again brought me milk, which I refused. First, they calmly insisted I should drink it. Gradually, their tempers rose, the shrew did her slapping stunt again, to no avail. Finally they relented and left the room, saying, “We are not going to let you die. You can be sure of that. We’ll get food into you even if we have to force it up your….”

Later a physician came in with a container of glucose to feed me intravenously. I swore at him. He responded coolly: “Why do you attack me? I’m not a torturer, I’m a doctor. I go to many government departments, this is one of them.” I blasted out at him again: “Shame on you. Accomplice of murderers, venal filth serving the murderous regime and its evil aims. Witnessing crime and remaining inactive is a complicity, let alone actively serving the criminals….”

When he came close, I kicked him and his assistant. The woman and the policemen came in and tried to hold me. Later others also joined in. At last the physician managed to give me a few injections and glucose feeding got under way.

I refused to take food for thirteen days and they had to feed me intravenously every day after a struggle. I had heard that the entrance of air into the vein could be fatal and hence I tried to force the physician into a mistake, struggling particularly hard when he was entering the needle into my vein. I later realised that it does not work, I kept up the struggle not to submit to their will, and not to make their task easy.

Physically, I felt extremely weak, drowsing most of the time, not knowing how many days had passed. The room would often fill up with uniformed thugs. Generals would come in their absurd uniforms, trying to talk me into submission, presumably hoping to overwhelm me with the ‘might’ of those scraps of metal gained not because of bravery, leadership quality, etc., but for flattery, for lack of any qualities, for servitude. Their underlings would stand to attention, like slaves who had accepted inferiority, at a cheap price. They all looked so ridiculous, I did not even have to make any special effort to mock them and describe their true nature and value. It would all happen automatically, without any effort. They would talk for a while, then, with their ‘dignity’ and ‘values’ harshly but objectively questioned before their subordinates, they would invariably cut short their ‘speeches of wisdom and authority’ and leave the room concluding: “This girl is crazy”. They also had a so‑called psychiatrist who had officially declared me insane!

*There is considerable ‘class’ difference between policemen and officers of police in Iran. The former are invariably from the masses, low paid and with little or no training, whereas the latter are well paid professional graduates of the Police Academy. (I.C.)

More Interrogation, More Torture

Two or three days after I was brought back to the Police Detention Center, Khatayi and Niktab came for interrogation. They were repugnant beyond imagination. Walking in with my file, they tried to appear confident.

“We don’t want the address at this stage. There are other questions. You talk, we’ll write. First your name”.

I looked at them with hate, remaining silent.

Silence.

They began mocking: “This one’s crazy her mind hasn’t grown….” “She’s trying to do a Leila Khaled* on us”. “Come on, tell us your name? We’ve got your birth certificate here, but we want you to tell us yourself”.

Looking at these mercenaries, dispensers of injustice, traitors to the people, would make my blood boil. They went out and came back with an electric prod. Giving me shocks: “What’s your name? You won’t talk, ha?” They gave me electric shocks for about an hour, looking more and more dismayed under the weight of my silence When leaving, they threatened: “This was only a joke. We’ll come back at midnight and the real torture will then begin”.

I was not frightened, but concerned. I wanted to be awake when they came. Under sedation and drowsy, perhaps I could not concentrate. However, they did not return that night.

The next few days were rather uneventful. I would sleep most of the time, and fight when they came to inject the needle for feeding with glucose solution. Some of my actions seemed quite childish, but I felt I had to resist them all the time, I had constantly to remind them that they were enemies and that I never would or could compromise or make peace with them.

One of the daily occurrences was the shrew’s slapping exercise. My nose would bleed and I would try to wipe the blood on the blanket with my hands cuffed, an act, which seemed to immensely displease and irritate the shrew. She would explode with anger, swearing at me, telling me that I was rude, devoid of manners, not having lived in a ‘decent’ society! She would pull my hair, jerk my head and slap me again. Another favourite punishment of hers was shamelessly to order the policemen to tickle me. That was most degrading.

Various officer torturers would come in from time to time, uttering some nonsense, having fun! These were in fact reminders of their baseness, stiffening my will never to reveal any information that would in any way help them and the criminal regime they represented to survive any longer. Niktab was the least bearable. This mercenary vermin was always uttering the foulest obscenities, trying to keep up the ruthless and savage criminal image that he had shown in my torture. Seeing him would draw a violent reaction in me and it was only with tremendous effort that, I could face him with pride and coolness. I wanted him never to come into the room. I was aware that they were always seeking a weak point to exploit, and I did not want to provide them with one. He had sensed my immense hatred. Once, entering the room he announced proudly: “Your executioner is here”, as if that pleased him. “You are all the same filth”, I retorted, “there is no difference between you thugs”. The truth of that struck me. Later I succeeded in remaining cool and composed with all of them, dismissing them all as the vermin they were.

Some of the officers coming to the room offered insulting sympathy when the jailer shrew was denouncing me as rude and uncivilised: “It’s not the poor girl’s fault. Who do you think her father was? Some pauper, a penniless worker”! Such occasions provided an opportunity for politicising the policemen in the room. When the villains talked of the toiling masses with such insulting arrogance, I would point out: “This is precisely why we have risen to uproot you. You and the regime you support are exploiting the masses, sucking their life‑blood as parasites, deceiving them, pretending you care for them and support their interests, and yet, you do not even have the decency to respect them for their toil, for carrying the burden of your regime’s existence on their shoulders….” Typically, the Shah’s henchmen would not even bother to defend the despot and his regime, or to justify its crimes. Their response invariably was to disassociate themselves from the regime, implying that they may even be against it but: “Alas, what can one do? One must make a little money, win a little bread….”

Going to the toilet was a major problem. In the first two days I was too weak to be moved, so they had to bring a chamber pot. Later they walked me to the toilet supporting me under my arms. Five women came in and the two policemen waited outside. The pipes attracted my attention, would I not die if I ram my head against the pipes? I tried to get closer to the wall but they were preventing that, as if they knew what I had in mind. I tried to pull myself free but I was wanting in strength and, besides, I could not stand up without their support and had to lean on them. They were holding my arms tightly. I could only move my head, so I attacked them butting their heads. The poor ‘tender’ and ‘fragile’, helpless women! Anyone of them would have been able to overpower me, but they screamed in panic: “Help, help, she is beating us up”! A bunch of officers and policemen invaded the toilet, grabbed me and handcuffed me. The women told the policemen to stay. I protested, demanded that they should leave, and tried unsuccessfully to force them out. I was taken back to the room and they did not take me to the toilet for the next few days.

*Leila Khaled ‑ a heroine of the Palestinian freedom movement

The True Face of the Villains

The day before Comrade Behrouz was arrested, a Major by the name of Makhfi came to the room as usual with his sick witticism. They were not seeking information now, but simply coming to torment me, to implement the foul thoughts that entered their morbid minds. Makhfi told one of the policemen to fetch a spoon and feed me the excrement from the chamber pot. The idea was so stupid and meaningless that I took it as a mere threat. The policeman came back with a spoon. They put the pot next to my bed and were actually going to carry out the order. I was so infuriated that I even forgot my hands were tied to the bed. I jumped to pick up the pot and empty it on the ruffian’s head, but with my hands tied, I fell over, tipping the pot over myself. The thug who had not anticipated my reaction and was very angry, ordered the policeman to rub the excrement over my face and pour some down my throat. They strapped me to the bed and carried out his order. The only thing I could do was to look at the animal with the utter hatred I felt. My eyes were burning in my head with hate.

It was a ridiculous situation. The vermin who were devoid of even the most primitive human values found it amusing. One officer after another would come to the room, laugh at me, utter some sick remark, leaving with a hand over their noses: “She has rubbed shit over herself. There you are, she is crazy”. The two policemen guarding me were complaining about the smell and the mess, holding me responsible!

I am not able to describe exactly how I felt then. While feeling proud, ignoring their utterances and dismissing the whole thing as yet another sign of the enemy’s frustration, I still felt the insults and humiliation and endured them in the sense that one forces oneself to do or not to do something, not because one is indifferent. I felt the insults, the disparaging remarks, with the whole of my being. I was inflamed with hatred. I would remember the life of all the deprived, oppressed people 1 had known, thinking: “I am of the People, my People. We are exploited together. We have been denied freedom and justice. We have been denied all the pleasures of life. Our lot has always been humiliation, insult. The parasite class, the regime these vegetables represent, and its imperialist masters, are the cause of our unhappiness and misery. I am of the People, my People. We are different from these vermin. We stand apart from these criminals, parasites, exploiters, and imperialists. We stand with empty hands but with hearts overflowing with hatred and hope. We stand apart from them. We stand before them with indomitable resolve, with belief in ourselves and in our final victory. We stand determined to fight. We stand to fight until their final and total destruction. Until injustice is ended, until exploitation is no more, until oppression is a thing of the past. The final victory will be ours. It cannot be otherwise….”

The Torture And Martyrdom Of Comrade Behrouz Dehghani